Pleasurable and anxious: the art of Justin Daraniyagala – Reviewed by Jagath Weerasinghe

12 Feb, 2016

Modernism in art is a world phenomenon. It is not an artistic acquisition specific to western civilization, although its rudimentary formulations can be traced way back to the Renaissance in the 16th century Italy. Modernism in art, as we know it today acquired its definitive configurations in the last decades of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century. From a world perspective, the visual lexis and the compositional structures of the modernist art in the west achieved their complex and revisionist particularities in an historical space that arose from the western encounter of the non-western societies. Modernism in art is both a result and a construct of colonial encounter/ confrontation of the Occident with the Orient and vice-versa.

While the modernist artists in Paris were busy defining the basic tenets of modernist art with cues, inspirations and motivations received from many non-western art traditions such as Japanese, African and Asian art, a similar process in the visual art was taking place in Sri Lanka. A process, as in Europe, which had arisen from the historical space that ensued from Sri Lanka’s encounter and confrontation with the non-Asian: the West. The Buddhist mural painters of the Gampaha and Colombo regions who painted visually vibrant, thematically dynamic, and stylistically different murals in shrine rooms of Buddhist temples such as Karagampitiya Subodharamaya in Dehiwala or the Galkanda Rajamaha Viharaya in Gampaha were registering a far-reaching transmutation in the mural art tradition of the island. Their murals marked the beginning of a different style within the Buddhist muralist tradition, definitively, while retaining the history of the tradition within it, both visually and thematically to a considerable extent.

Can we name this ‘new’ style in Buddhist muralist art ‘modernist’? Probably not, since such a categorization doesn’t express the social and political complexities of this ‘new style’ in the Buddhist muralist tradition. Modernist art requires the artist to be conscious of their art to be modern. Nevertheless what is important for our discussion is the fact that the colonial encounter/confrontation charged a new vision in visual art in the island, and looking back from the vantage point of the 21st century one can see that this encounter/ confrontation actually gave rise to four distinct art trajectories in the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century. The ‘different style’ in the Buddhist muralist tradition, which I have already mentioned, is one such trajectory (actually this can be called a sub-trajectory within a larger and a wider movement of changes) and the other three can be defined as following: the easel painting tradition that made constant stylistic references to British academic realism and that which was largely the prerogative of the English speaking elite of the time; the consciously nationalist modernist artists who were inspired by the Bengal school of art of India; and the consciously modernist and radical artists of the 43 Group. While all the four trajectories can be seen as ‘modern’ in some form or the other, depending on how one looks at modernity in visual art, what is absolutely clear is that the first truly modernist group of artists in colonial Sri Lanka were the artists of the 43 Group, because they were conscious about their position and the role in the art making world of Sri Lanka as ‘modern artists’, and they posited their artistic and creative personae as anti-establishment and anti-colonial. Their politics in art making was diametrically opposite to the tastes promulgated by the colonial ‘ruling block’ of the time. Defiance and non-compliance, I’d argue, is necessarily a defining ingredient of being modernist in art.

The 43 Group was an eclectic composition of artistic styles and temperaments. This is a quality that makes them a politically interesting grouping of artists. The rationale that bound them together was the imagining of the nation by way of a range of artistic styles and thematics that dwelled out side of the taste and command of the colonial ‘ruling block’. This also made them the most innovative group of artists to emerge in south Asia in the middle decades of the 20th century. The artists of the 43 Group presented us with a range of styles that were selectively inspired by modernist developments in art of the School of Paris and produced an indigenized expression of modernism in art of great ingenuity. The 43 Group is a distinctly Sri Lankan achievement in art that could encapsulate the intellectual and emotional depths of social, political and cultural consciousness of the time they lived and worked.

We are not a society that publishes much on modern or contemporary art. We really are very poor in that! Not publishing on Sri Lanka’s achievements in modern and contemporary art is almost akin to an intellectual crime we commit on the future generations of artists and art students of the country. Sri Lanka still doesn’t have a proper public collection of 20th century paintings. We are the only nation in the region that doesn’t have a museum or a gallery for modern and contemporary art. The ‘silver line’ that occasionally punctures this murky situation is the publishing of well researched, well documented, and beautifully designed books on the 20th century artists by a few committed individuals who have realized the value and importance of presenting the achievements of 20th century art of Sri Lanka to the public and the future generations. It can’t be emphasized enough on the importance and need of such publications on Sri Lankan art in a country where there is no proper public place to see art. Several good and interesting books have been published on the artists of the 43 Group. Monographs have come out on George Keyt, Ivan Peries, Richard Gabriel, George Claessen, and now a new book on another 43 Group artist Justin Daraniyagala has come out. These publications make it possible for us to see the Sri Lankan achievements in the 20th century, at least in print.

The monograph on Justin Daraniyagala, a publication of 204 pages and 150 color plates, is a kind of challenge to the readers. The image in the dust cover of the volume is itself a challenge. An elongated blackish figure of a woman with closed eyes stretches across the cover while the head of an old man in profile looks at us (?) from behind the blackish woman. What an unexpected way to present Justin! Women in Justin’s paintings are generally beautiful, pleasant and anxious, but on the cover of the monograph we meet a different woman altering our perception of the artist. The life and works of Justin Daraniyagala that we encounter in the pages of this volume will further alter our understanding of this great master of 20th century Sri Lankan modernist art.

The manner of narration deployed in the monograph demands an engaged interaction with images and the text since the story of Justin Daraniyagala is narrated by three different authors and the images are presented within thematic groups; not chronologically. Three narrations by three authors with three different relationships to the artist: a researcher, a friend and another artist. They relate their encounters with the artist and his work from three different temporal loci. Shernavaz Colah, who is also the editor of the volume, takes us through every stage and phase of Justin’s creative life/ career. She paints a detailed canvas of the artist’s life. Neville Weerarathne’s narrative takes us briefly into the artist’s life by way of describing his intimate alliance with the 43 Group of which he was a founding member. Weerarathne presents us with snippets of Justin’s intelligent and critical personality. Ranil Daraniyagala engages with Justin’s work soon after the artist’s death in 1967. Then there is a whole chapter by Justin himself on appreciation of painting. This chapter of the book is a window that allows us to see the mind of the artist through his own words. Justin’s ideas and thoughts on art making, as revealed in this essay is erudite. He has internalized the basic theoretical tenets of classical modernist art and in his paintings one can see how he has deployed those theories and techniques of art making in a challenging manner. The narrative structure of the volume demands the reader to be creative, critical and engaging. The complexity of Justin Daraniyagala’s work and life, I would say, demands such an approach.

The volume’s first chapter, titled Justin Daraniyagala, the artist and the man 1903-1967 by Colah illustrates different phases of Justin’s life. Here she successfully links the different phases of the artist’s life and his thoughts and ideas on art with his paintings. While meticulously narrating the artist’s life through different phases of his life, she contextualizes Daraniyagala’s work within the broader art historical backgrounds: both traditional Sri Lankan and the avant-garde in Europe and India. Colah’s finely descriptive and illustrative text allows the reader to walk with the artist through his life and work. Her essay, while being consciously celebratory of the artist’s life and achievements, opens up small windows for us to sense the anxieties of the artist and the avant-garde art world of Colombo at that time in history. The anxieties that lurked beneath the surface of Colah’s text gets clearer and substantiated in the essays by Weeraratne and Justin himself. The inability and the reluctance that the mid 20th century art-consuming audience of Colombo had shown in grasping the artistic achievements of artists like Justin Daraniyagala (or Ivan Peries) was a historical failure on the part of the art audience of that time. But, what strikes a particular chord in me as a practicing artist is the persistent and continued inability of Colombo’s art-consuming audience, even today to grasp the achievements of the avant-garde or the art that is different!

Ranil Daraniyagala’s essay, ‘Justin ’, written in 1968 and reproduced in this volume presents us with a solid and reliable text to mark the contours of Justin’s highly complex artistic career in terms of its chronology and thematics. If not for this essay by Ranil, we would not be in a position to order Justin’s work in some chronology (Students in art history should be most indebted to the editor of the volume for reproducing it here.) Ordering an artist’s work chronologically helps one to understand more closely the trajectories that the artist had taken and dropped at different points of his career. Justin’s art in terms of its style and themes are highly varied. He has been working in and experimenting with several styles. Ranil’s essay helps us to grasp Justin’s highly complex body of work within a certain framework that is both chronological and thematic.

The catalogue of paintings in the volume gives a comprehensive account of his work that shows Justin’s stylistic navigations. He has always been seeking and changing. The surprising discovery that one may encounter in this volume is that Justin had pushed his style and method of painting to an extreme that had resulted in a totally non-figurative and abstract painting. This is an intriguing aspect in Justin’s career. That’s a Justin we had never known before. It is true that his work is built on a strong understanding of abstraction, but seeing a complete abstraction by Justin is a challenge to our understanding of this great modernist master. This is one aspect of Justin’s artistic career that remains a total puzzle, which none of the authors have addressed. Perhaps, that’s because engaging with a subtle and difficult issue like this requires a very different approach to art history, which is out side the purview of the present volume.

It would not be a bad idea to briefly compose my thoughts on Justin’s abstract work at this point. Generally speaking, the 43Group artists were figurative artists in a wider sense. In other words they were not that much attracted to abstraction as an end in itself. But George Claessen of the 43 Group has been different. He did several extremely interesting abstract/ non-figurative works during his career. Ivan Peries’ work, while being very abstract in terms of composition and in the manner he treated human and natural forms, remained within the pictorial frames of being figurative. Up until now, these two artists, as for me, presented the two ends of the scale of involvement that the 43 Group artists had with abstract or non-figurative painting. With the current volume on Justin, we see that Justin too had been grappling with the issue of abstraction in a different manner than George Claessen or Ivan Peries. Classen’s abstractions are poetic and lyrical, and in contrast to that Justin’s abstractions are loaded with a latent energy that may be dibbed as ‘wild’. They are made of strong and untamed strokes and splashes of colors. What is so interesting to note is that his non-figurative abstractions, even though they are a few in number, hold the entire spectrum of intensities, anxieties, and temper that constituted the core expression of his figurative works. Justin seems to have approached the issues of abstraction form two distinct perspectives. Like in some of his best figurative works, his abstractions are also composed within a geometric structure that forms the basic design holding the painted forms. Then in the abstract works titled ‘Composition’ in plates 39 and 40 of the current volume, we encounter a different approach to abstraction. In ‘Composition’ in Plate 40, Justin has embarked in to the realm of ‘pure painting’: painting as painting. This work captures everything that is Justin Daraniyagala the artist. In this work Justin has totally freed himself from the grip and the command of the nature, the visible world, and his own history as an artist! Amazing!

Justin remained mainly a figurative painter throughout his career even though he had produced a few remarkable abstractions as we see in the catalogue published in the current volume. I have often wondered why some figurative artists having pushed themselves to the point of abstraction shun away from it? One famous example in this regard is Henri Matisse of School of Paris. Like Justin he too embarked upon abstraction but didn’t stay there. Reasons for this could be very complex and complicated. But, in the case of Justin the politics of the time could have been, among other things what prevented him from going further into abstraction and staying there. Like most of the 43 Group artists, Justin too was engaged in the grand struggle for regaining political independence back from the British. Artists of the 43 Group engaged in this struggle from two distinct perspectives. The most popular one was the Orientalist perspective; the best example for this is George Keyt. Justin, like Ivan Peries, stands out from the rest of the 43 Group artists, in terms of his imagination and representation of ‘Ceylon’ and the ‘cultural-time’ he lived and worked in as manifested in his work. His imagination, as we see in his vast body of works has not been fashioned and determined by Orientalist aspirations and politics. In that sense Justin Daraniyagala has not been an accomplice of the colonial ideology. This is how I see him from his work reproduced in this volume.

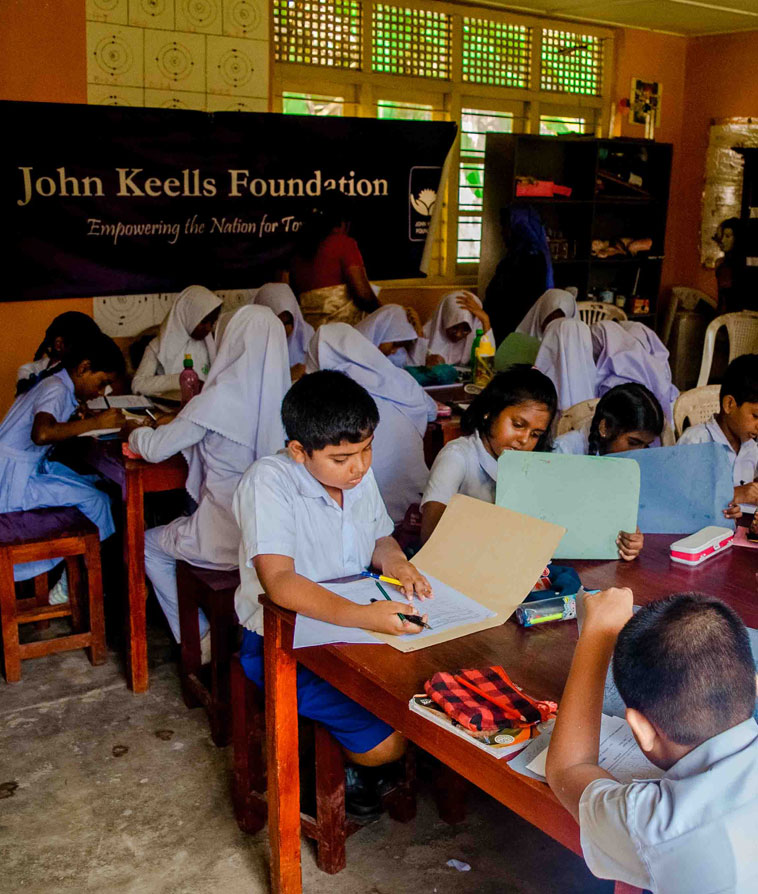

: John Keells for Green Environment

: John Keells for Green Environment