- Home

- NEWS

- Incandescence, Humanity and Modernism: The Art of Justin Daraniyagala – Reviewed by Ashley Halpé

Incandescence, Humanity and Modernism: The Art of Justin Daraniyagala – Reviewed by Ashley Halpé

12 Feb, 2016

Encounter with the art of Justin Daraniyagala ignites in the sensibility that undergoes that experience an especially powerful sense of making a discovery that Edmund Wilson called The Shock of Recognition – the intensity, depth and force of the experience validates the use of the metaphor of a shock.

It happens over and over again with the Daraniyagala oeuvre. There is no effect of repetition and certainly none of habituation, so that each encounter is indeed truly personal, which is what makes each unique. These paintings and the few drawings included in the book demand that the visitor to the exhibition spend time, even hours it may be, with each.

Possession of the book enables a surrogate experience of such a visit. The core of the book is, after all the splendid collection of expertly printed plates, each needing the same concentrated attention as a painting or drawing at an exhibition. This is made all the more necessary since, as Arjun and Siran explain in their Preface, the family were denied the opportunity of setting up their own gallery in which the art of Justin Daraniyagala could be permanently housed. Such a gallery would have given us the chance of having regular, extended encounters with the paintings and drawings.

They reveal the whole sad story. The land for the gallery was originally available at Horton Place, and the family had the vision and the will to build the gallery. But the march of social history nullified the realization of the gallery project and the dream. Crippling death duties swept away a large part of the family income, even necessitating the sale of the land on which the gallery was to have been built.

Sadly, since Justin Daraniyagala himself died without issue and the vision of a gallery had to be abandonned, the collection had to be divided among the heirs.

The untimely death of Ranil Deraniyagala, whose very important study is included in this volume, removed from the scene another possible active participant in the project. It was left to Arjun and Siran with, as we find, the able assistance of the former’s daughter Yvani, to take the long view. This ample volume is the magnificent result.

Of course it is still not impossible for a foundation on the lines of the George Keyt Foundation to be set up to take over the running. But as things stand, the dream remains unrealized and the vision unfulfilled.

To turn to the volume itself, its core is of course the magnificent collection of expertly printed plates. The book gives us the first publication of Justin Daraniyagala’s essay, The Appreciation of Painting, discovered posthumously, a Preface by Arjun and Siran Deraniyagala, a very substantial biographical essay, Justin Daraniyagala – the artist and the man. 1903-1967 by the Indian critic and journalist Shervanaz Colah, written with the assistance of Arjun Deraniyagala, an appreciative Foreword by the art collector and philanthropist of art, Sir Christopher Ondaatje, Ranil Deraniyagala’s careful study of the paintings and, at the end, a carefully constructed Biograhical Note and an Epilogue by the prime movers of the publication project.

Ranil Deraniyagala’s fine study offers a valuable model for proceeding beyond the first rich experience of the individual works plate by plate. He takes us, as it were, on a guided tour through the collection.

He categorizes the paintings into nine groups with a preliminary prelude, “The 1940 Group,” in terms of his intuitive perceptions of the stylistic links between the paintings in each such group under the heading Relatedness of Style – A Suggested Methodology.

He then crosses his own lines in a series of challenging cross-references, carefully listed on P. 151. For instance, he tells us ‘Consider then…Fig. 31 first in relation to Fig.18, then to the 1940 Group’ Figs. 40 & 41 occupy Group VI and their relatedness is immediately noticeable. In another case, he cross-references Figs. 23 and 25, inviting us to compare them too to the pictures in Group II (which contains five pictures) and goes on to say ‘Also observe their relation to Fig. 9 and Fig. 42 as regards the weightiness of the figures.’

Thus his presentation is, one could say, dialogic, evolving an arrangement by imagining a friendly conversation with a serious browser who would actually bring to each plate the concentrated attention I spoke of as necessary.

The present writer has had all three important kinds of important encounter with the works. First, the immediate direct experience of the few paintings by the artist that can be viewed at the Sapumal Foundation galleries along with the same kind of experience of the plates in this volume. Secondly, he has undertaken the exploration by Group suggested by Ranil Daraniyagala. Thirdly, he has worked through the cross-referencing Ranil Deraniyagala suggests on page 151.

The result has been two-fold. I have gained a deep familiarity with these works, a vibrant inwardness with them and, indeed, the world of Justin Daraniyagala.

I have also gained an immensely rich education of my sensibility, of my sensitivity not only to art but to our immediate world, our Lanka in its multifarious forms and full palettes of colour. I have undergone an existential rebirth of my inner self.

While this was taking place, I stumbled on a very special quality of the art of Sri Lanka, one that it shares with the Lankan ambience, its very air.

The paintings of the great Sri Lankan artists all have a certain radiance which appears in its intensest, most penetrating form in the incandescence that is a major characteristic of the great works of Justin Daraniyagala.

Incandescence. Breaking free of all classifications, I pass from Maternity (Pl.1) to Fish, Mother and Child, Girl with Goldfish and on to

Plates 5,6,7, 8-12, 14, 15-32. ( I also comment on details of many of these paintings further in my presentation.)

They give a distinct impression of being lit from within by an indwelling spirit. Since we had the same feeling in the smallest conversation with the man, the spirit is the spirit of Justin Daraniyagala himself pulsing with a singeing energy in painting after painting. It is present too in the portrait by Aubrey Collette included in this volume.

In a very large number of the paintings the incandescence coexists with a deep humanity. This binds the mother and the baby together in the curve of the mother’s body in Maternity (Pl.1), in the embrace and the gaze of the mother enclosing the child who casually clasps a fish in Fish, Mother and Child (Pl.2), the subtle visual intimacies of the man, the woman and the child in (Pl.3) – Untitled – forming a whorl of links in the upper central area of the painting with an unexpected downward flow of muscular tension of the woman’s right arm as she reaches down – fondly, we feel – for the tiny tortoise crawling towards her; the indescribably tender closeness of the Blind Mother and Daughter (Pl.5), the beautifully unexpected caressing of the body of the sitter by the placing of the impastos in the study of a seated nude on page 35, the direct openness of the gaze of the subject at the viewer in Girl With Goldfish (Pl.7), the solicitude with which the attendant female figure (is it the mother?) regards the Bride in the painting by that name (Pl.8), the interacting gazes of the human figures behind the goat in Notes on a New Mythology – the Goat (Pl.9). This humanity is to be felt not only in the relationships between figures but also in a certain quality of absorption in the subject perceptible in the eye of the beholder of a series of studies of heads (Plates 45-51), of paintings on the Mother and Child theme (Plates 1-4), and three of Lovers (Plates 22-24). It is present, too in the painting of a standing nude (Pl.55) which richly evokes the earthy fleshliness of an indigenous female body. This is all the clearer when we note the artist’s perception of the almost anaemic quality of the flesh in Blue Nude (Pl.54). We see that we have to ignore the anecdotal implications of the identification of it being a portrayal of the celebrated contemporary of Justin Daraniyagala, Anais Nin.

The adventurous creativity of all these paintings compels one to try to place the art of Justin Daraniyagala in the international modern movement, since venturesomeness and passionate creativity are hallmarks of the avant-garde.

The art of modern Sri Lanka has been defined by diversity and animated by a restless, experimental search for authenticity of utterance. We had the radical developments that led to the formation of the ’43 Group and the parallel courses struck out by others such as David Paynter, Nalini Jayasuriya and George Bevan. At the same time there was the major reorganization of the teaching of art in the schools by C.F.Winzer and W.J.G. Beling. After thirty years of such activity the important artist and art educator, Jagath Weerasinghe was impelled to say “ …the post- colonial historical condition is such that it has made us inhabit, quite cheerfully, an ahistorical social space. Contemporary Sri Lankan art is an expression of this social, political and cultural condition.” The present writer has developed this subject at length in his The Contemporary Art of Sri Lanka for The Art of India ed. Frederick M. Asher, Encyclopaedia Britannica Pubns. (0-85229-813-7).

The contemporary artists of Sri Lanka have responded to a riven reality and fractured consciousness in a variety of ways making their art distinctly modern.

Here, one needs to heed the important remarks by Georges Besson who called this art, especially the art of Justin Daraniyagala “… one of the important revelations of our time.” Donald McClelland reviewing the Daraniyagala Exhibition at the Smithsonian Institute, wrote that it was “… one of the most significant movements in Eastern art today…Its importance lies in the synthesis of traditional art form and those deriving from the West which has produced painting truly Eastern in inspiration yet of universal validity…” G.S.Whittet went so far as to say that paintings like Maternity of 1947 “…contain an abrupt shock of contact with the facts of life which reduced the new Picasso at the Tate Gallery, Femme Nue to a voluptuous but withdrawn boudoir decoration…” Shervanaz Colah stresses that the paintings in this book show that Justin Daraniyagala’s art is an important revelation in twentieth century art. We add to this the lines defined by Justin Daraniyagala himself in his essay The Appreciation of Painting.

“At the end of the volume the Epilogue by Arjun and Siran Deraniyagala tells us, among other things, the sad story of the gallery project’s decline from lively hopefulness to a seeming abandonment.”

Neville Weereratne has written a substantial study of this book which includes a careful reference to our predecessor in critical appreciation, Ellen Dissanayake. Albert Dharmasiri has also expressed his admiration of this volume. I am happy to join them in hoping that as Neville Weereratne puts it, a gallery will be built some day to enable the reassembling of the whole great collection “… to ensure the safety of this great inheritance of the people of Sri Lanka for the rest of imaginable time.”

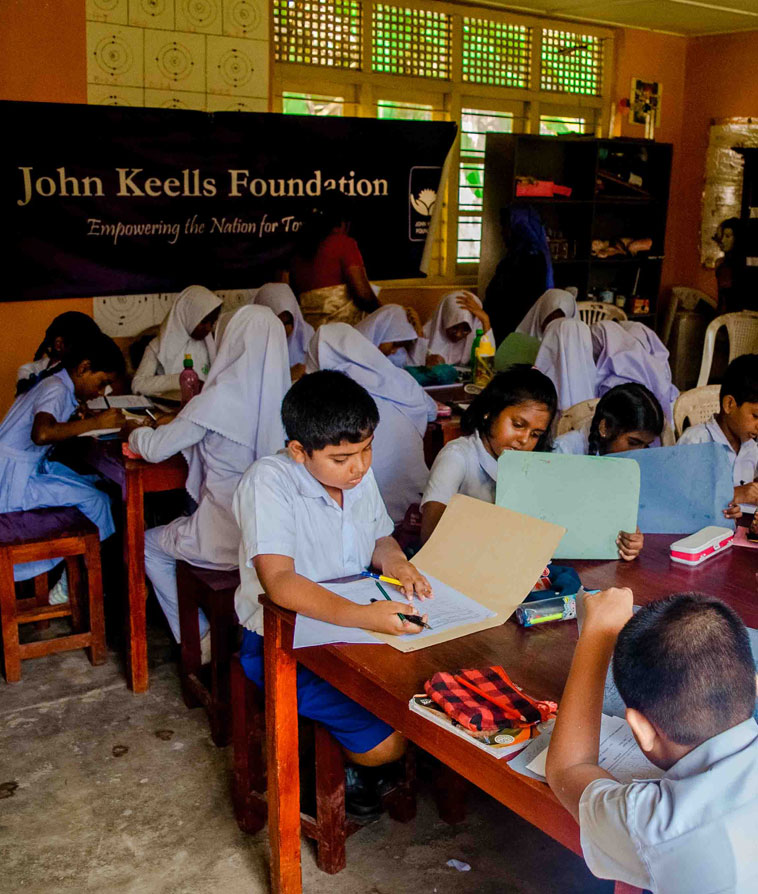

: John Keells for Green Environment

: John Keells for Green Environment